Though the New Year might start on January 1, and the calendar puts mid-March as the start of spring, May is when it finally feels like winter is over. In England and North America, May and June also once meant the return of an exciting seasonal celebration: the strawberry party.

Jane Austen’s 1815 novel Emma depicts a June strawberry party hosted by the landowner Mr. Knightley. With the help of the boorish Mrs. Elton character, the reader gets a good idea of what strawberry parties of the time could look like. Mrs. Elton gushes about the large bonnet she will wear, and the little basket decked out in pink ribbon that she will carry to pick strawberries in Mr. Knightley’s garden. “We are to walk about your gardens, and gather the strawberries ourselves, and sit under trees;—and whatever else you may like to provide, it is to be all out of doors—a table spread in the shade, you know. Every thing as natural and simple as possible,” she says.

While the sensible Mr. Knightley firmly insists on eating indoors rather than outside, strawberry-themed festivities often did have a picnic quality to them. These events hearkened back to the 18th-century French fête champêtre. Translated as “countryside feasts,” they were were elaborate parties with a rural theme, held outdoors. Hosts realized that, in a rapidly industrializing world, “natural and simple” activities such as strawberry-picking were a great idea for parties.

Americans quickly picked up on the idea. In Six Months in America, written by the English Godfrey Thomas Vigne and published in 1832, Vigne describes a strawberry party in Baltimore, held at “a country house, surrounded by gardens and pleasure grounds.” Unlike Austen’s bucolic berry-picking, this event was more like a ball, with attendees arriving at the host’s home in the evening. Attendees waltzed on the lawn until it became too dark, then danced inside until almost midnight. To refresh themselves, writes Vigne, the dancers had “strawberries and cream, ices, pine apples, and champagne.”

Possibly the most famous enjoyer of strawberry parties was Mary Todd Lincoln. “For the last two weeks, we have had a continual round of strawberry parties,” she wrote to a friend on June 26, 1859. She herself had just hosted 70 people for a strawberry party the week before.

“One had to throw good parties and invite the right people,” says Laura F. Keyes, a librarian and historical presenter who performs as Mary Todd Lincoln for educational events and lectures. When Abraham Lincoln decided to get back into politics in the late 1850s, she explains, Mary helped with her hostess skills. “A little bit of business would be done at that social function. She understood that,” says Keyes. One of the few Mary Todd Lincoln dresses still in existence, she notes, is a dress covered with a printed strawberry pattern at the Abraham Lincoln Presidential Library and Museum.

By the end of the 19th century, strawberry parties had become a standard part of the American social season. They were called by a number of different names: strawberry teas, strawberry revels, and strawberry fêtes. Strawberries and cream and strawberry shortcake were standard refreshments at these events, along with strawberry ice cream and strawberry lemonade. As to why people chose the strawberry as the focus of these entertainments, Keyes has a theory. “A lot of modern audiences might forget that there was no refrigeration as we know it now back then. So the strawberry party was to indulge in all this fruit before it spoils,” she explains.

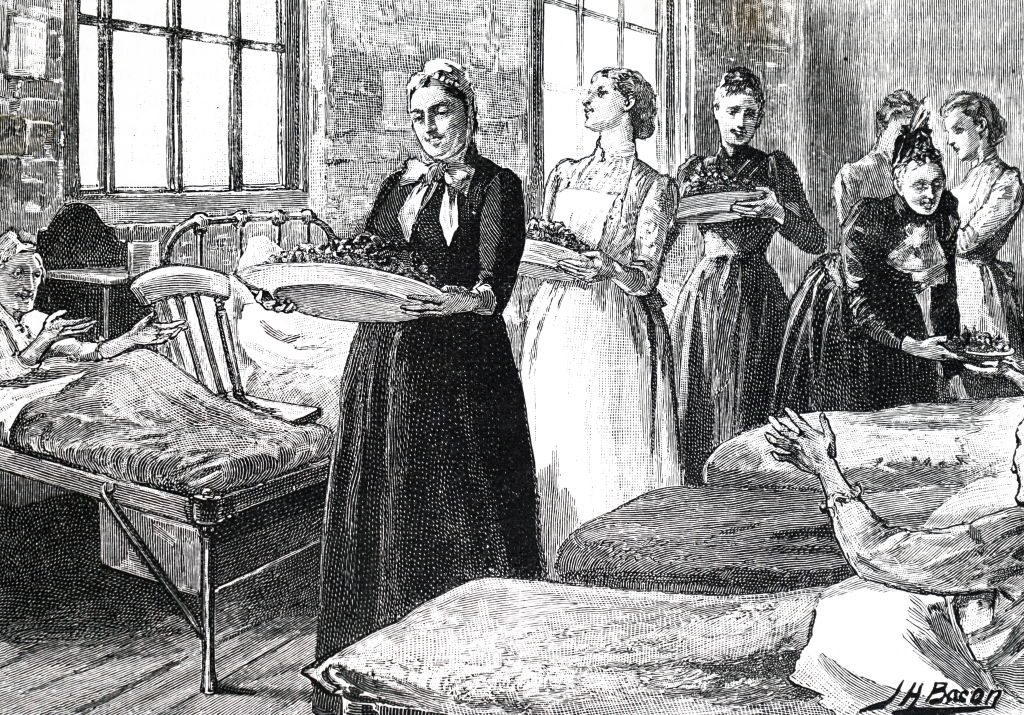

These celebrations could also take a number of forms. Some had the attendees picking strawberries themselves, while others simply served them to eat. It wasn’t just the wealthy or fortunate who got to enjoy a strawberry feast, either. Charitable groups held strawberry parties for invalids and wounded soldiers, and by the 20th century, they had become a standard way of raising money for churches.

These events were not glittering balls, like Vigne’s 1832 depiction, or rustic berry-picking events. Usually, they were held indoors. In 1904’s Entertainment for All Seasons, the author Louise Dew gives instructions for holding a strawberry regale, an event “so potent in swelling the funds of needy churches.” Dew suggests decorating a church parlor with roses and strawberry plants, and writes that “strawberries should be served in every style and form—strawberry ice-cream, strawberries and ice-cream, strawberries and cream, strawberry whip [a kind of pudding], fruit lemonade, strawberry vinegar, strawberry shortcake, [and] strawberry sherbet.” The waitresses, she suggests, should wear green gowns and white aprons, and there should be tables set up to sell strawberry preserves and take-home shortcakes.

Many strawberry fundraisers followed the same formula: waitresses in cute strawberry themed outfits (occasionally with hats shaped like strawberries), all kinds of treats for sale, and floral decor. After a while, these events became almost painfully routine. A 1901 book of fundraising ideas noted, dryly, that “when time rolls around annually for converting strawberries and cream into Church money, the longing arises for something novel to assist in the process.” Their suggestion was to hold an “international strawberry festival,” with volunteers dressed up and performing as women from around the world and a hall decorated with “the flags of all Nations.” This, suggested the author, would add a “spice of excitement and fun, generally conspicuously absent on these festive occasions.”

At secular strawberry parties, there were often more games involved. One magazine suggested a strawberry race, with players competing to carry strawberries on dinner knives from one table to another. One 1907 book gave out a number of berry riddles for party-goers to answer for a prize. (For example: What berry is a domestic fowl? Answer: A goose-berry.)

These days, people aren’t holding strawberry parties for 70 guests in their homes like Mary Todd Lincoln. But strawberry festivities are still going strong. Many regions host strawberry festivals in the spring and summer, celebrating their local harvest of the fruit. And, surprisingly, a number of institutions regularly hold strawberry-themed events. The New-York Historical Society first held a strawberry feast in 1856 and still hosts an annual Strawberry Festival lunch.

Interestingly, some historical societies have made strawberry parties a new tradition, in order to both fundraise and educate visitors about Victorian-era festivities. This year, on June 2, the Winnebago County Historical and Archaeological Society will be hosting their second annual Strawberry Party at the historic Morgan House in Oshkosh, Wisconsin. Keyes will be in attendance, portraying Mary Todd Lincoln in her party-host prime. To her, these events have an appeal that transcends time. “The strawberry party is truly just a celebration of this fantastic fruit,” she says. “It was a way to not only celebrate it, but to indulge in it. And I mean indulge in its most positive sense.”

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.