Like many middle-aged women I know, I spent my summer parsing the rallying calls of personhood and artmaking ringing out from the new roster of divorce books—books like All Fours by Miranda July, Liars by Sarah Manguso, and Splinters by Leslie Jamison. Books that, if you ask my carpool buddy, my hairdresser, or my neighbor, feel juicy, arousing, deep, uncomfortably accurate, and sometimes a little tone deaf. “Must be nice to leave your husband and retire to your second residence to make art,” says my friend who finally has a day off to retain a mediator after splitting with her husband last year. Some of my divorced friends never attempt pursuing child support. Why bother? they think. You can’t find the money a narcissist stashes in all his hoarded musical equipment, or account for the cash a deadbeat collects under the table.

Article continues after advertisement

We now have this new cadre of divorcees offering narratives for how to navigate ambition, domesticity, and artmaking. We have popular, sexy, intelligent, feminist voices blowing the conversation open. But what if you don’t share the privileges of this well-connected literati? What can we learn from a predecessor who endured without visibility or support from the literary establishment?

The truth of this story is that I pulled out a bundle of letters I had shoved in the back of my closet and ended up kneeling there on the floor pulling pages from their envelopes. The return address read Lee Holleman McCarthy, Bakersfield, California.

I had kept these letters for twenty years, bundled in twine, but had forgotten all about them. I had forgotten the ways this older, gifted woman had saved me when I was a writer just starting over in my twenties, newly sober and reeling from the kidnapping and rape of my younger sister. But there was Lee’s perfect cursive opening up before me, unspooling in letter after letter when I could finally decipher what she had been trying to tell me.

Her dispatches were inscrutable to me when I was younger. I skimmed past her difficult wisdom—notes about a gutting divorce, the time suck of her “mothering instinct,” her feelings of being stuck in a gutter of irrelevance. But now that I’ve crossed over into midlife, I recognize her dark humor, her disappointment, her depth, her—as Louise Glück calls it—“majestic fatigue.”

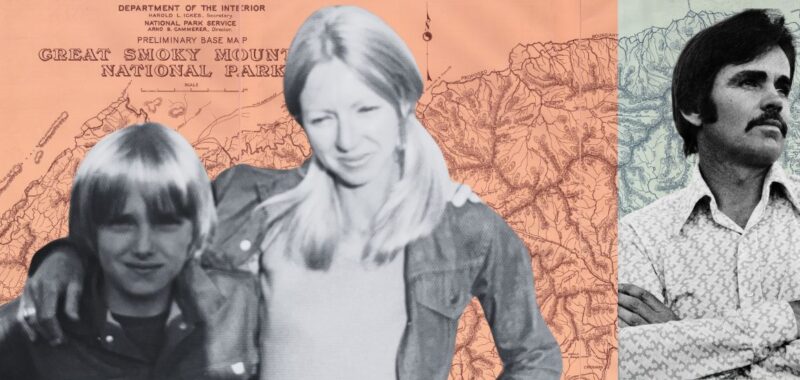

Picture Lee in 1963, coming home to a simple wooden cabin at the base of the Smoky Mountains. Beside her is a struggling writer named Cormac McCarthy. The newlyweds cross the threshold with their infant son and try to become a family. You can hear katydids, crickets, and tree frogs. You can hear a nearby creek flowing into Little Pigeon River.

The coupling doesn’t last long. Lee will eventually leave and head West, telling her version of the split in a poem I heard her read again and again. Transported back to “the front porch of a farmhouse near Pigeon Forge,” she says: “You don’t act as if you want a wife and baby. You act as if you want to be single again.”

“I guess that’s right,” the man says. I picture Lee packing a suitcase that she drags to the porch where Cormac waits.

“But what will you do?” the man in the poem says to Lee, “Be a whore?”

I’m sure it takes just a moment. Then Lee is back in the house. Her jaw tight. Her stomach on fire. She wouldn’t be crying. She would be kicking a pair of boots out of her way. I see Lee sliding the mattress, dragging it onto the front lawn. She can’t find gasoline, but she’s looking. “I tried to burn the mattress” she writes. She tries to incinerate the centerpiece of their domestic life. Rest, time, the sheets softening each week, Lee wants to light it on fire.

When Lee left, she had only what she could take with her. She was young, naïve.

Many of us are well acquainted with the mythology of Cormac’s penniless writerly origin story. In Richard Woodward’s 1992 profile of him in the New York Times, he asks Cormac if he ever paid alimony, “‘With what?’ Cormac snorts” (at least Woodward uses the verb “snorts” to describe Cormac’s response), and then Cormac excuses his lack of involvement by reminding Woodward of his evictions in the French Quarter and how he and his second wife (the one who agreed to become his personal secretary and retype his manuscripts for him) would swim in the lake for a bath.

We also now know that Cormac was poor on purpose and that he will eventually fall in love with a 16-year-old girl the same age as his and Lee’s son, convincing the girl that Lee’s clan “detested” him and “forbade them from being together.” Yet when I’m combing through the depositions Lee gave during the censorship battles she fought as a schoolteacher in the 1970s and 1980s, she testifies that she tried for many years to reconcile with Cormac, her only son’s father.

When Lee left, she had only what she could take with her. She was young, naïve. Not only did she leave without literary connections, but she was also the sole support, financially and otherwise, for their infant child.

Displacement, desperation, and small children. This could describe many new mothers, but especially those who are working long hours, mothering alone, scraping a life together. Unlike the narrator of Miranda July’s All Fours, most women are not minor celebrities; most of them don’t own their homes, let alone net over a million dollars in estimated market value. They’ve got compound interest and tedious jobs. If they have artistic ambition, they paint in small notebooks they can stash in their tote bags. They hole up in their bathrooms writing on the floor. Or, like Grace Paley, they jot notes on the backs of receipts they keep in their apron.

Lee ended up finding work as a schoolteacher—she stepped onto a train, a suitcase in one hand, a baby in the other, and chugged ahead into her new life with no idea where she was going or how she would survive.

But survive she did.

She provided for her son without any child support from Cormac. She won a landmark free speech battle in Central California where she put down roots. And, eventually, she found her way back to her art, writing novels, stories, articles, reviews, and publishing two books of poetry in her fifties and sixties.

Since rediscovering Lee’s letters, I’ve flown to Tennessee and returned to the site of her formative loss. I built an archive of transcripts and documents that attempt to verify an alternate path for artmaking, one that stands in contrast to the lone genius, and that precedes the exits made by the new cadre of divorcees. Lee left before it was easy or normal to leave. She left in 1963.

That same year, across the ocean in England, Sylvia Plath was taping the door to the nursery shut so the carbon monoxide from the oven she would use to kill herself wouldn’t seep in and harm her children. Plath was unmoored by so many things—mental instability and misguided medical treatment—but also by the loss of Ted Hughes, the loss of the dream of her marriage.

When I first met Lee in the late 1990s at a magazine launch in Ojai, California, she stood at the podium, her blonde hair falling across her face like an ancient beauty. I could feel a charge of loss and desire coiled inside her, disguised by a cashmere wrap dress. I had just taken my seat after reading a poem that opened with an image of me climbing scaffolding with my boyfriend to sleep on top of a building.

Titled “Letter to An Ex-Lover” the poem chronicled a time when I thought that if I just kept driving, I could outrun my pain, and how this lover and I panhandled in the Mission District in San Francisco right before I ended up in the hospital with a botched abortion. Eventually I crawled back home to my parents. Shortly before I met Lee, I had been docked in my childhood bedroom, my head shaved, big saddlebag hips, listening to the hum of the refrigerator as I turned in bed from drug and alcohol withdrawal. Lee recognized a fellow survivor, and after signing my book, she told me to send her some of my poems.

Lee’s life deepened her art, and her art deepened her life.

I was partly saved then by Lee and then I was saved again in midlife when I found our letters. As I began writing about Lee, I finally recognized her ambition, all her disappointments, and her remarkable tenacity. Lee was eventually awarded a Stegner Fellowship in fiction but once it was over she headed back to the San Joaquin Valley to resume teaching. She couldn’t stay at Stanford even though she was offered a class to teach. Her invisibility, her class status, her itinerancy created a fragility which made it difficult for her to capitalize on her small successes. She couldn’t sacrifice security and go all in with big artistic risks. So how do you survive as an artist when you lack time, resources, an established career, and literary connection that can amplify your work?

Lee found her way forward through a devotion to mentorship, service, and friendship. Her life was netted by an interconnected web of relationships, desires, all inseparable, all threaded together, that added potency and depth to each other. She kept up a massive correspondence with people across the country and worked against the scarcity mindset of capitalism by lifting up other writers.

In an article she wrote for the Los Angeles Times she traces the camellias newspaper publisher Elias Manchester Boddy bought for the Descanso Gardens’ estate back to her friend (another single mother and writer), poet Amy Uyematsu’s grandfather, right before he was put into a Japanese internment camp. “Her article was a wonderful recognition of Grandpa Uyematsu,” Amy said, “who Lee admired deeply—and in Lee’s masterful style, she also managed to put in a nice plug for my poetry by including excerpts of poems about Grandpa.”

Lee would swim in the airport motel pool in Bakersfield like a character from Joan Didion’s Book of Common Prayer. When she could afford it, she travelled to Mexico and Europe over the summer. During her summer breaks from teaching, she wrote scripts, novels, short stories, poem after poem: “A story in two days, another story in two more days.” “Revision” she says in a letter, “is as much of an act of grace as the first draft.” In other letters, she’s concocting a writers’ conference (“Save a week in July next summer, okay?”). Her apartment filled with piles of her writing and stacks of books. She became, as she wrote to John O’Brien, “a dragon lady whose den is not rubies and bones, but paper.”

Lee’s life deepened her art, and her art deepened her life. As I retype her poem “The Geology of Home” what’s most striking is the way she describes her mother’s relationship to the land, the physicality of it, the way her mother embodied the land. In the poem, what is hidden inside is made visible, externalized. What’s external is taken inside and alters the way she sees.

I’m coming to understand Lee’s relationship to the land as being connected to that daily translation of the world made new, a recovery of perception, a revivification of ordinary moments—which is one way of defining artmaking. It’s like picking up the call echoing through the wilderness, a call that awakens something dormant and alive. It’s a humble and daily practice—one that’s a reward in itself and that will likelly have to suffice for most of who endeavor to make art.

When you live a life that takes you close to the edge, it’s easy to feel like you’ll always remain on the outside, like you’ll never be permitted access. Addiction, divorce, trauma, financial precarity—you feel like something has slammed shut. You feel shattered, lost, and invisible. When Lee signed her book for me when we met under the oaks at that first reading, she wrote “For Kim: fellow poet who knows if the door stays locked in spite of everything try a window.” Lee knew about locked doors. Retrieving the story of her life can teach us about what it takes to find a way in.