1.

The last time it happened, I was driving the family home from my mother-in-law’s house and saw a big animal at the side of the road with its legs up. Something about the corpse, frozen in the shape of a last action like the statue of some Greek myth, sparked an acute feeling of sadness for all the pain that goes on every moment around us, the kind of suffering against which most of us are powerless. I once read that to obtain the purest definition of compassion, think of a parent with no arms or legs whose child is drowning.

I said nothing to my wife and daughter about the dead deer. I just kept driving. Then, as often happens, my mind began to hum and I was flooded with the most vivid story details: characters, setting, and even a final scene I could work back from. Not everything, but enough to get started. It’s how every book or story begins for me. In the past it’s been a boy sitting outside a casino in Las Vegas wearing only one sock; a partially sighted woman in a Long Island department store feeling the items on the rack.

I don’t choose what to write; I’m chosen. And writing is not something I particularly want to do or look forward to. It’s not a hobby, but a coping mechanism for the emotional chaos of our world that is difficult for me to reconcile without telling stories.

When language started becoming a means to an end, rather than an end in itself, a feeling of doom set in.

I knew from experience I would have about five days to sit down at the typewriter and nurture the small flame of the dead deer into the fire of my next story. That is, if I didn’t want the story to choose someone else.

2.

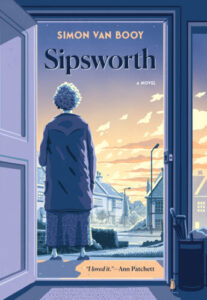

Back in late 2021, when I began the book that would become Sipsworth, (my tenth work of fiction), I wanted to try something different, buck my usual process and take control of the narrative instead of being guided by something external, like the dead doe or boy with one sock.

Railing against a comment made by E.M. Forster about characters taking over the writing of a novel, Nabokov referred to his characters as “galley slaves.” It’s a troubling image of course, and I should have steered clear, but the core idea of controlling every fictional character from start to finish was alluring. Imagine not having the anxiety of forcing oneself to write with only a vague idea of what’s going to happen? I could save myself sweating through those dozens and dozens of pages that get thrown away because in the end they stall the pacing and don’t serve the plot.

I could sit in Le Crocodile, a hotel café near my apartment, with Earl Grey and plan the entire book, chapter by chapter, scene by scene. Nothing would be left to chance. How could there be any flaws in a story arc that was carefully planned?

My God, I let myself imagine, this could become a bestseller! If the entire story was pre-planned, why not introduce trending themes, elements that ensure the success of commercial novels? If I pushed through any resistance and just wrote the thing, I could cry later watching my friends and family cannonball into the pool of our new Hamptons cottage.

Of course, as you may already realize, I thought I was at the gates of heaven, but I was actually on my way to the other place.

Fairly soon into my “new process” I realized I wasn’t so much writing as impersonating a writer called Simon Van Booy.

What I wrote did not become my next novel; instead, it was the worst writing of my career.

3.

If you’ve got enough experience as a writer, this type of writing I attempted is possible. But it’s an awful experience day in, day out, sitting down to work. Like trying to make the most delicious meal when you’re not hungry. When language started becoming a means to an end, rather than an end in itself, a feeling of doom set in—everything I typed steered my project closer and closer to the iceberg.

When you’re telling the right story, there’s a kind of excitement, a powerful feeling of agency and obsession.

Enter Sipsworth, my pet mouse. Or rather, exit Sipsworth.

The poor fellow, who would sometimes fall asleep on my desk as I worked, had been ill for months and was suffering, so I took a few days off from “writing” to consult with the vet and sift through the many mouse books I’ve accumulated. In the end, I know what I had to do, which didn’t make it any easier to accept. We booked one final appointment with the vet, where, in a treatment room with Ikea chairs and the faint aroma of bleach, Sipsworth and I would have one last play session, one last peanut, one last cuddle.

In the moments before he died, Sipsworth was curled up in my hand. I think he was grateful at being freed from the pain of his tumor because he gnashed his teeth in a way he used to as a young mouse when he was experiencing pleasure.

The vet put Sipsworth’s body in a small box with some tiny flowers. He looked as though he was resting. We closed the box for the first and last time, then drove back to our apartment to dismantle Sipsworth’s home and put away his toys forever.

A few days later, I was back at the desk impersonating myself when Sipsworth appeared. I couldn’t believe it, but there he was at the end of a paragraph, where the main character was supposed to be falling down steps (according to my plot outline) but had stopped the moment before tripping, because from under a box on the other side of Rue Lepic, someone very small was staring at her intently.

There was no mistake. The soft gray body. Pink paws. Mona Lisa smile. It was Sipsworth. And just like that, I went back to my usual process of writing—like catching a wave that suddenly appeared and was big enough to ride for whatever this new book was to become.

A few weeks later the old plot outline was completely redundant. I think the only thing I kept was somebody shouting from a window in chapter three. I wasn’t upset because when you’re telling the right story, there’s a kind of excitement, a powerful feeling of agency and obsession and fierce determination to get the story down before allowing the editor version of yourself to take over from the artist-self too early.

Having the confidence to allow my beloved dead mouse to take over the novel that now bears his name is one reason I feel comfortable calling myself a writer, and not simply someone who writes.

__________________________________

Sipsworth by Simon Van Booy is available from David R. Godine Publisher.