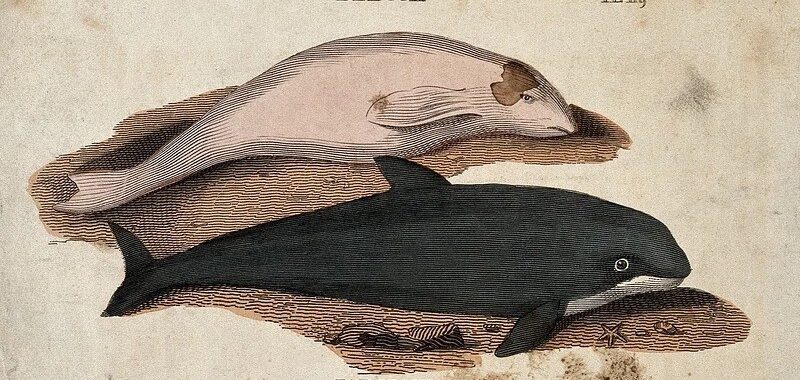

As the vast glaciers of the last ice age retreated toward the poles some hundred centuries ago, most of the small, playful white whales that had foraged at the southern edge of the glacial mass migrated northward to the Arctic seas. Several thousand stayed behind, having found a bit of stable habitat at the mouth of what would eventually be called the St. Lawrence River, a deep channel of cold, fresh water flowing northeast from the Great Lakes basin to the Gulf of St. Lawrence off the Labrador coast.

Here, the mixing of massive liquid volumes causes an upwelling of micronutrients, supporting a diverse food chain. The St. Lawrence beluga whale, cut off from the rest of its species, thrived here for millennia near the apex of the ecological web. During summers, female belugas and their young ascended the tidal river while a mostly male population of adults swam near its mouth. In the winter, both groups retreated to the loose-pack ice regions of the lower estuary and gulf.

Singing, squeaking, squealing, chirping, clicking, whistling, whirring, and mooing to one another, beluga whales form a noisy society. Their varied vocalizations resound through air and water, as well as the hulls of ships, inspiring the old sailors to call them “sea canaries.” Beluga pods range in size from a few individuals to a few dozen, and their social affiliations are loose, often transient.

Together, sometimes in perfect synchronization, their white bodies slip through the water forward, backward, surfacing, spouting, and diving—sometimes deeper than twenty meters below the surface—in pursuit of a variety of prey: big fish, like salmon and cod, but also sandworms, shellfish, squid, octopuses, and schools of little fish. When the whales are not chasing meals, they often chase one another, in what scientists describe as social locomotor play. Belugas are among the species that researchers have observed playing with toys in the wild, including found objects, exhaled bubbles, and living things found in their waters.

And so the beleaguered St. Lawrence beluga had a new enemy: the American showman.

Orcas were the principal predators of beluga whales in the St. Lawrence River until humans migrated to its shores. Then, for at least several thousand years, indigenous people hunted the beluga from open-top canoes, driving them into the shallows and dispatching them with spears. When French explorer Jacques Cartier made his second exploratory voyage up the St. Lawrence in 1535, he noted the presence of both the Iroquois hunters and the snow-white whales, describing the latter as delicious.

Basque sailors joined the beluga hunt in the 1600s, building fixed weir nets on the mudflats near the river’s mouth; when the tides went out, the whales would get trapped in the meshings and become easy prey for the hunters. French colonists followed, and, after receiving a white-whale fishing concession from French administrators, many found the commercial harvest of whales for their oil and skins to be a lucrative occupation. The introduction of harpoons and guns in the nineteenth century accelerated the slaughter, and, thereafter, the local whale population suffered a steep decline.

Even when the species was still common on the St. Lawrence River, the beluga whale was an extreme oddity to the landlubbing New Yorker, several hundred miles to the south. The creature’s slippery, deep-sea strangeness, its perfect pallor, its size, its thrilling association with ancient tales, its incongruity in the industrial dry-land cityscape ensured that, should one ever splash within city limits, the populace would be helpless to look away from the spectacle. Is it any wonder, then, that the idea of bringing a beluga whale to the heart of the metropolis, to be feasted upon by the public gaze, became an animating ambition of museum owner and impresario Phineas Taylor Barnum? As he would later recall in his autobiography:

In 1861, I learned that some fishermen at the mouth of the St. Lawrence had succeeded in capturing a living white whale, and I was also informed that a whale of this kind, if placed in a box lined with sea-weed and partially filled with salt water, could be transported by land to a considerable distance, and be kept alive. It was simply necessary that an attendant, supplied with a barrel of salt water and a sponge should keep the mouth and blow-hole of the whale constantly moist. It seemed incredible that a living whale could be “expressed” by railroad on a five-days’ journey, and although I knew nothing of the white whale or its habits, since I had never seen one, I determined to experiment in that direction. Landsman that I was, I believed that I was quite as competent as a St. Lawrence fisherman to superintend the capture and transport of a live white whale.

And so the beleaguered St. Lawrence beluga had a new enemy: the American showman, who would stop at nothing to have the charismatic cetacean on display in his museum. As with his other animal attractions, Barnum seemed to relish the challenges of capturing and conveying the whales to New York—elaborately griping to reporters about the hardships and expenses he suffered in the effort, reinforcing the rarity and value of the animals to a breathless public eager for new amusements.

After preparing an eighteen-by-forty-foot tank made of brick and cement in the basement of his American Museum—for “the reception of the marine monsters”—Barnum himself undertook the trip to French Canada, where he contracted local fishermen to assist in the capture of at least two beluga whales. They constructed a large V-shaped weir, or “kraal,” made with wooden stakes, and waited several days for two whales to enter the trap together during high tide.

When a beluga pair finally wandered into the stockade, fishing boats blocked their retreat with splashing and yells until the tide went out, so that, in Barnum’s description, “the frightened whales would find themselves nearly ‘high and dry,’ or with too little water to enable them to swim, and their capture would be the next thing in order.” The fishermen secured heavy ropes around the whales’ tailfins and dragged the helpless creatures out of the water and into separate seaweed-lined wooden crates. The crates were then loaded onto a sloop and sailed upriver to Quebec City, where they were loaded onto the special railcar Barnum had hired for the long trip back to New York.

The showman had already provided a thrilling account of the whale hunt to newspapers in Quebec and Montreal, and telegraphed communities along the train route announcing the impending arrival of the crated whales. “The result of these arrangements may be imagined: at every station crowds of people came to the cars to see the whales which were traveling by land to Barnum’s Museum,” Barnum crowed, “and I thus secured a tremendous advertisement, seven hundred miles long, for the American Museum.” Upon the belugas’ arrival at their destination, a writer for the New-York Tribune gushed, a “real live whale is as great a curiosity as a live lord or prince, being much more difficult to catch, and far more wonderful in its appearance and habits.”

The possibility of seeing a whale in New York City stimulated a curiosity so implacable… that the moral sense could not be engaged.

Barnum’s advance publicity effort ensured that by the time the whales sloshed into their ice-cooled tank, in the dank basement of the American Museum, thousands of New Yorkers crowded the entrance, impatient to lay eyes on the great “white whales.” They would have to hurry: These two belugas would not be at the museum long. “I did not know how to feed or take care of the monsters, and, moreover, they were in fresh water, and this, with the bad air in the basement, may have hastened their death, which occurred a few days after their arrival, but not before thousands of people had seen them,” wrote Barnum, with evident overall satisfaction, in one of his autobiographies.

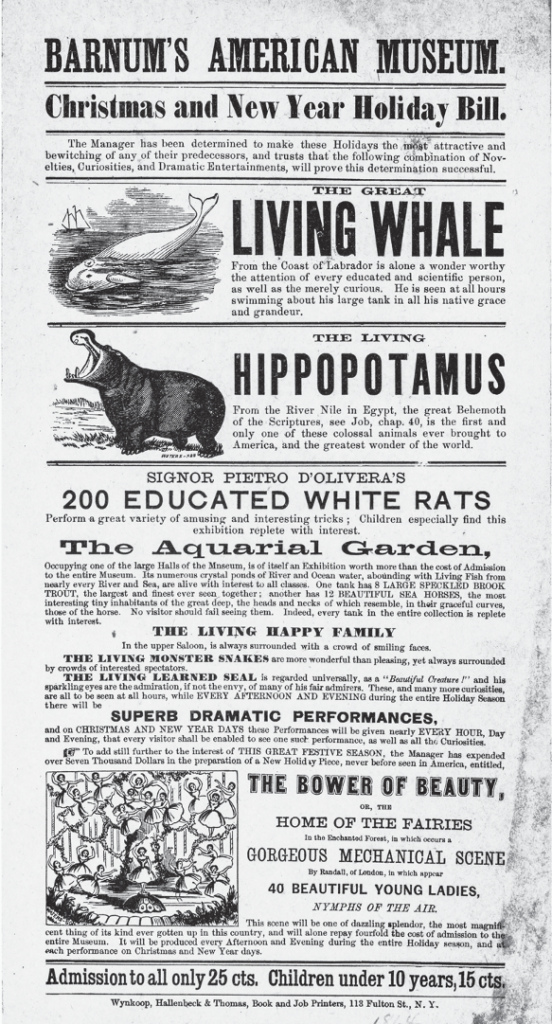

Barnum’s American Museum handbill, 1864.

Barnum’s American Museum handbill, 1864.

Barnum being Barnum, he “resolved to try again.” Weeks later, he had installed a new tank made of slate and thick glass plates, twenty-four feet square, on the museum’s more commodious second floor. Fresh water from city taps was replaced with murky brackish water from the mouth of the East River; Barnum had situated a steam-powered pumping apparatus at the harbor’s edge and laid a network of iron pipes under city streets (with the purchased permission of a Manhattan alderman) to ensure that his next two Labrador whales bobbed before visitors in a circulating supply of untreated harbor water.

Alas, these whales quickly died as well—“their sudden and immense popularity was too much for them,” Barnum later quipped. If museum visitors were troubled by the serial cetacean fatalities, it did not deter them from paying their twenty-five-cent admission fees and lingering in the second-floor galleries to behold their short-term antics. And so, Barnum continued to exhibit whales on the second floor of his museum, one pair after another, in cheerful, morbid succession. “NOW IS THE TIME to see these wonders,” declared a newspaper advertisement announcing the most recent arrivals in 1865, “as THEIR LIVES ARE UNCERTAIN.”

It is disconcerting to see that phrase there, in stark capital letters, and to imagine how little it seemed to have troubled the moral sense of the man who paid to have it printed—to say nothing of the countless men, women, and children drawn to the museum in droves by this grim sales pitch.

Perhaps the most charitable way to imagine it is that the possibility of seeing a whale in New York City stimulated a curiosity so implacable—the irresistible pull, in an era before it was easy to visit zoos or aquaria or travel long distances, of seeing creatures that had been brought so far, with a physiology so enormous and strange—that the moral sense could not be engaged. But that supposition makes it all the more remarkable that, by the following year, the arrival of the animal-welfare idea would render such flagrant disregard for animal suffering and death in a New York newspaper advertisement nearly inconceivable: arguably illegal, but perhaps more important, unfashionable.

__________________________________

From Our Kindred Creatures: How Americans Came to Feel the Way They Do about Animals by Bill Wasik and Monica Murphy. Copyright © 2024. Available from Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, LLC.