On the first day of practice of the 2021 season, Galvin Drake pulled into the parking lot of the California School for the Deaf in Riverside, music blaring. The thumping beats of Daft Punk and Damian Lazarus were so loud it seemed as if they could loosen the bolts holding together his green 2005 Toyota Camry. Galvin couldn’t hear the melodies or the lyrics, but it didn’t matter. Music had a different meaning for him than it did for hearing people. The beats pulsed through his seat. He didn’t listen to music; he felt it. Late at night when he would drive near his home in Riverside, Galvin would turn it down, as a courtesy for his hearing neighbors. But on campus, he let it rip, often with the windows open.

Article continues after advertisement

Galvin was the assistant varsity football coach at the school, or CSDR, as everyone calls it. He was the team’s enforcer, lecturing the players on the importance of weight lifting and eating well. No junk food and soda during football season, he told the student athletes. He looked the part. He could deadlift 405 pounds—not 400, but 405, he noted—and had the bulging muscles to prove it. He ended his text messages with a flexing biceps emoji. But on this first day of practice he was worried. The pandemic had forced the cancellation of football the year before, and everyone had languished in front of computer screens, attending their classes remotely on Zoom and playing video games when class was over. Many of the players were overweight. All were out of shape.

Most days, Adams did not need to ask for his players’ attention: it was ingrained in Deaf Culture.

The pandemic set back millions of students across America, but for deaf children it was especially hard. Many lived in homes or neighborhoods where no one spoke their language. School was the place they found peers, they learned to advocate for themselves, they came out of their shells. “When COVID happened, all they had was this little tiny screen on Zoom,” one administrator at the school said. “School was their access to the world.”

Keith Adams, the burly head coach of the football program, with a shaved head perpetually tanned by the California sun, could relate to what the pandemic had done to his players’ bodies. He had gained thirty pounds himself. On day one of practice, Adams arrived with cases of Gatorade that he had bought at Costco to ward off dehydration. He was determined to get his players into fighting shape.

*

August in Riverside can feel like the inside of a pizza oven. Unlike the California coast, which benefits from the natural air-conditioning blowing in from the Pacific Ocean, Riverside is one mountain range away from the Mojave Desert. To avoid the worst of the heat, the coaches had scheduled their first weeks of practices for the evening, when temperatures typically fell into the low nineties. The players had a name for the first days of conditioning: Hell Week.

Phillip Castaneda didn’t have far to travel to get to practice. He walked across the street from the Target parking lot where he had slept the night before, tucked into the back seat of his father’s Nissan Sentra. He cast an eye at his new teammates. They were greeting one another like long-lost relatives. High school students get only four years to prove themselves on the football field. This cohort would get only three. The cancellation of the previous year’s season had made the players hungry to play again, to be teammates again, to block and tackle. They had missed the physicality of the game that came so naturally to them. In the plainest of terms, they were restless boys who wanted to hit again.

The first day began with Coach Adams gathering the team for orientation meetings in the air-conditioned bliss of the athletic facility. This could have been a meeting of any football team in America, coaches and players sitting on plastic folding chairs in a colorless classroom discussing their hopes for the season. But there was an important difference for the Cubs, a kind of inescapable togetherness. Teenagers, boys in particular, are known for their adolescent grunt years, for eyes-cast-down, monosyllabic conversations.

This was rarely the case in Cubs meetings. Communicating in sign language required unbroken eye contact; it demanded that a listener watch not only the hands but also the slightest nuances in facial expressions. When Keith Adams reminded his players, as he did so often, that the team would succeed only if everyone did their job, all eyes were on him. Most days, Adams did not need to ask for his players’ attention: it was ingrained in Deaf Culture. The boys were, by necessity, locked in.

Much of what the team discussed on this first day was practical. Face masks were obligatory inside, Coach Adams told them. School was back in session, but the coronavirus still stalked students and teachers. Write your name on your water bottle and don’t share it, he said. Only eight people allowed in the weight room at once.

The weight room, which had two heavy doors that automatically locked unless you found a way to prop them open, ran along a corridor that led to the locker rooms. When one stood in that hallway looking through the sealed-shut windows, it was nearly impossible to hear people inside the weight room. But this was no obstacle for the Cubs. They could effortlessly converse through the thick glass, one person signing in the hallway to another inside using the weights.

If it had been a hearing school, a student might be able to bang on the door loudly enough for someone to open it. That wasn’t an option for the Cubs. No one would know you were knocking. The Cubs were window people, not door people. Window versus door; it was a leitmotif in deaf art and literature.

The majority of the players on the Cubs came from deaf families, giving them added stability at home.

At the team’s first gathering, Phillip could see the strong family element at the very core of the Cubs: the team’s star quarterback, Trevin Adams, was the son of Coach Adams, and Trevin’s younger brother, Kaden, was also on the team. It was a dynamic that gave Coach Adams all the more incentive to succeed. Keith Adams was both coach and father. As for Trevin, who had inherited his father’s stockiness and drive, no one—not players on the team or their adversaries—would ever question why he was quarterback and not someone else. From his time playing in little leagues and in middle school, Trevin had always shown an outsized talent and passion for the game of football.

After the team finished its meeting, the players headed out to the school’s rutted grass field ringed by a dirt track. Coach Adams and his assistants split them into four stations, where they would run various drills. They did calisthenics and footwork. Then Adams assembled the team at the goal line and told them to sprint back and forth across the field. In eight-man ball, the field is shortened to 80 yards, so they went to and fro, 160 yards at a time.

The players stood at the goal line for these, their first sprints of the season. Among them were Trevin; Jory Valencia, a stringy wide receiver whose brother, also deaf, would soon head off to Europe to play professional basketball; and Felix Gonzales, the most versatile player on the team, on the short side but very fast. All three had been teammates in middle school, and they, with a few other players, were the heart of the Cubs. They, like other players on the team, had also benefited from more stable childhoods than Phillip Castenada’s. Their parents had a variety of mostly middle- and working-class jobs: teacher, mechanic, Amazon warehouse worker, carpenter, mail sorter at the post office, hotel housekeeper, substance abuse counselor. In the United States, more than 90 percent of deaf children are born to hearing parents, a stark communication barrier between mother, father, and child. Parents and their sons or daughters spoke different languages. But the majority of the players on the Cubs came from deaf families, giving them added stability at home: they could communicate effortlessly with their parents in American Sign Language.

Phillip was already out of breath from the previous set of drills, but he wanted to show his new teammates his speed. He was five feet, six inches and 130 pounds, a lightweight in boxing terms. But he was so fast that Felix Gonzales would later remark that when he ran, it looked as if he didn’t have legs, like the roadrunner in the cartoon.

Phillip ran the sprints hard but then suddenly took a detour off to the side of the field. He fell to his knees and retched. He got up and then threw up again, so many times, in fact, that he felt like a human water fountain, kneeling and gurgling on the sidelines and worrying that the coaches and his new teammates were looking at him as a lost cause. But he was not the only one. Ten players, nearly half the team, vomited in practice, some of them dashing to the locker room to heave in the relative privacy of a bathroom stall. Cody Metzner, the team’s veteran running back who had lifted weights at home during the pandemic, kept his lunch down. But he was panting for breath, feeling awful, and nearly passed out.

Coach Adams was alarmed. Players at other schools had been able to meet for conditioning during the pandemic. But CSDR was a boarding school as well as a day school. The students who lived in the Riverside area commuted every day to school and could have theoretically come to practice. But the boarders at the school came from across Southern California: San Luis Obispo near the coast, Bakersfield in the Central Valley, San Diego along the Mexican border. They had gone home during the distance learning phase of the pandemic. There had been no way to get the team together.

Coach Adams decided to cut short the two-hour practice after just half an hour. It was a small team, just twenty-one players, and he couldn’t afford for anyone to quit. The coaches were also worried about pushing the players too hard in the heat. A year earlier, a fifteen-year-old football player in Riverside County had died from heatstroke after an intense round of sprints.

This was an inauspicious start for the season, Keith Adams thought to himself. For the entire pandemic lockdown he had been awaiting the day when he could energize this football program. They had suffered losing seasons—more losses than wins—for the past eight years. In fact, since the CSDR football program began in the 1950s, the Cubs had been tormented by loss. The archives showed the football team had managed just nine winning seasons, and a handful of years where they won and lost an equal number of games. But they had fifty-one losing seasons. And in nearly a dozen of those, they had not managed to win a single game.

__________________________________

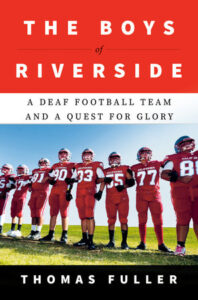

Excerpted from The Boys of Riverside: A Deaf Football Team and a Quest for Glory by Thomas Fuller. Reprinted by permission of Doubleday, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Thomas Fuller.