“We have, especially in the Western world, come to understand ourselves as our brains,” says historian Elsa Richardson. While the brain is viewed as the seat of the mind, the stomach is often relegated to the status of a mere “workaday organ,” Richardson adds, with a purely physical function and no part in defining our identity. However, expressions like “strong stomach” and “trust your gut” hint that this was not always the case. As recently as the mid-20th century, the human stomach was believed to exert a powerful and direct influence on mood and personality: You were what you ate, literally. This is one of the major themes of Richardson’s book Rumbles: A Curious History of the Gut, which comes out in October. “Are we our brains?” Richardson asks. “Or is it a little bit more complicated than that?”

A lecturer in history at the University of Strathclyde, Scotland, Richardson describes herself as “a historian of the body and the self,” researching how our understanding of who we are changes across time. In Rumbles, she traces the gut’s history in Western culture, and the various ways the organ has been conceptualized: from the medieval scholars who sought to balance the four humors of the body (and thus the mood) through eating, to the 19th-century doctors who thought of constipation as the root cause of illness, to modern wellness culture centered around a garden of gut flora.

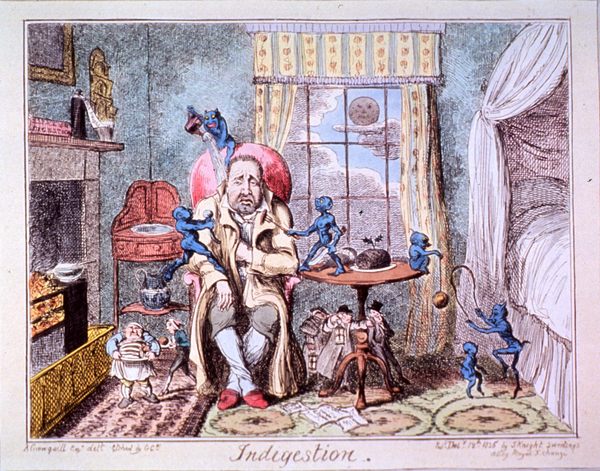

As an organ that takes in and processes the outside world, the stomach was historically believed to play a role in how we perceived and understood it. Scientists now recognize the existence of the enteric nervous system (ENS), or “second brain,” a network of neurons in the digestive system. Primarily involved in the unconscious process of digestion, the ENS communicates directly with the brain, and may have a role in emotional response or other functions that are still not well-understood. But when you look at historical medical texts, says Richardson, “it becomes clear that we have long, long recognized a link between the gut and the mind, or the gut and the emotional life.” The gut’s influence was even believed to extend to the subconscious, with nightmares blamed on indigestion well into the modern era. “You may be an undigested bit of beef, a blot of mustard, a crumb of cheese, a fragment of an underdone potatoe,” an incredulous Scrooge tells the first of his ghostly visitors in A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens, published in 1843. “There’s more of gravy than of grave about you, whatever you are!”

Gastro Obscura spoke with Richardson about our ever-changing view of the stomach and how what we say about the organ reflects what we say about ourselves.

Out of all the organs of the body, what makes the stomach unique?

There’s one sense in which [the stomach] is central to our being. We are on two sides of openings in the alimentary canal, which follows through the whole body. As the philosopher Stanley Cavell has it, to be human is to be “strung out on both sides of a belly.”

We think of the brain as being this miraculous feat of creation that lives within our skulls, and the gut, we might think of as being less sophisticated. I think that’s a false assumption because, actually, our gut does a lot more than we give it credit for.

How weird is eating, when you think about that process? It feels completely everyday, but it’s actually completely extraordinary. It’s this way in which we bring the outside in, and transform substances which are radically not us, into substances which are us. Decisions around what to eat and what not to eat have never been purely medical. One of my ways into the gut, from the beginning, was thinking about it as this site of contested, competing knowledge. There’s knowledge from the medical world, but it has to always exist in competition with household wisdom, or just the demands of your appetite; the desires that you might have when you’re out in the world for things that smell delicious.

As scientists have learned more about the stomach over time, how has our perception of the organ changed?

There seem to be distinct cultural epochs in the ways in which the stomach is imagined. If you go back into the medieval period, bodies were imagined as a great house, in which every part has its role and its function within the household. But the stomach is particularly important, because this is the bustling kitchen of the house which is keeping everybody else fed.

In the early part of the 20th century, the gut is talked about in much more derogatory terms. There are doctors who describe the gut as the cesspool of the body, or as a possibly defective drainage system, or a storehouse of poisonous, nasty bacteria.

I think we have a much friendlier view of the gut today. There is really a big shift in the language around the gut from the early part of the 20th century to now, when we tend to speak of the stomach in quite ecological terms. The gut is a garden, and we have responsibility over keeping that system in balance and being a good caretaker. There’s a lot of focus on balancing the gut microbiome, and there’s a lot of wellness culture framed and marketed around exactly that.

Historically, how was the stomach believed to affect personality and mood?

I’m completely obsessed with this book by Thomas Cogan called The Haven of Health, which is from the 16th century. It’s one of the first self-help diet books, in a way. Cogan is offering advice related to all health matters, but a large chunk of the book is taken up with lists of anything you could possibly imagine, and the effect it will have on you if you eat that.

He’s working within the humoral model: the idea that there are four elements within the body, and that health can be achieved by balancing those elements. If you had an excess of black bile, you’d be more likely to be a melancholic type of person. And you would want to eat things that were hot and spicy in order to create balance, because they would be opposite to melancholic, which is dry and cold. Cogan also writes that you should be very careful around eating turnips, because they are an aphrodisiac, and likely to make you excessively amorous. Likewise, he says that young men can eat goat meat, but old men should avoid it, because it would lead them to become angry and irascible.

Who are some other key historical figures that you encountered in your research?

Someone that recurs frequently throughout this book is my favorite 18th century physician, George Cheyne. He was a Scottish doctor who moved down to London in the early part of the 18th century to start up his practice. He had to wine and dine patients and various contacts, and he became very ill from all this overeating and over-consumption; so much so that he was, at one point, covered in these horrible seeping ulcers and was unable to walk unaided. So he put himself on this diet which involved eating only milk, roots, fruits, and vegetables. Quite a strict regimen–apart from [the fact that] he also specifies to his reader that they should restrict themselves to only one pint of wine a day.

He writes this book called The English Malady. For Cheyne, the English in the 18th century are all suffering under an epidemic of melancholy and nervousness, and he prescribes this dietary regimen that is intended to cure those melancholy emotions. Cheyne, for me, is really interesting because he’s writing for a popular audience. Today, if you go to the Self-Help section of any bookshop, you’ll find lots and lots of material about how to eat for good gut and emotional health. Cheyne is almost a precursor to that kind of literature.

How does culture affect the way we think about our stomach?

From the ancient world into the Middle Ages, the gut was thought to be literally prophetic. You could examine the entrails of animals, and from there, be able to ascertain information about the future. With the Scientific Revolution, those kinds of practices started to become increasingly viewed as superstitious. But rather than disappearing, instead, they become almost like [modern] diagnostic practices. At one point, you would be able to look into the entrails of an unfortunate dead goat, and foresee a vision of future events to come. When that no longer becomes possible within culture, the gut then becomes something which doctors look at to diagnose or predict illness in their patient. I’m thinking about things like looking at urine for a uroscopy, to better understand what the patient’s health was like, but also to foresee any potential future problems for them.

A villager in the Middle Ages might think that it’s possible for demons to lurk in your stomach, and that when you have a bad dream, there are demonic forces in your gut producing gaseous vapors, which rise up to your brain and cause the nightmare. If we think about that as one way of imagining the gut that is distant in time, we can reflect on how our own understanding of the gut might also be informed by culture. For me, the gut is fascinating in the way that it is shaped by the culture it sits in, but also always seems to be speaking back to and reforming the culture around it.

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Gastro Obscura covers the world’s most wondrous food and drink.

Sign up for our email, delivered twice a week.