The artificial intelligence boom isn’t just consuming massive amounts of energy and water: It’s also creating an unprecedented tsunami of electronic waste.

According to Stanford University, private investment in AI went from $3 billion in 2022 to $25 billion last year, with companies adopting AI tools faster than ever. This surge is forcing data centers to continually upgrade their hardware, discarding still-functional equipment in a race to maintain competitive edge.

This massive use of components to fuel the hardware that runs AI models is throwing off millions of tons of discarded electronic components. A new study published in Nature by a team of researchers from China, Israel, and the UK estimates that large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT, Claude or LlaMa alone could generate 2.75 million tons (2.5 million tonnes) of e-waste annually, severely increasing the environmental impact of AI.

“In the optimistic scenario where LLMs become ubiquitous (i.e., everyone uses it on a daily basis such as social networks), the results indicate that the EoS e-waste stream from designated data centers would rise to approximate 16 million tons (Mt) within a decade from 2020 to 2030,” the research reads.

The waste stream is growing at an alarming rate, with a compound annual growth rate of 110%—dramatically outpacing the 2.8% growth of conventional e-waste like screens and washing machines.

The geography of this crisis is highly concentrated. North America leads with 58% of AI-related e-waste, followed by East Asia at 25% and Europe at 14%, according to research from the Chinese Academy of Sciences and Reichman University.

Besides the huge amounts of electronic waste, the AI industry in general is consuming enormous amounts of resources. Last year, Decrypt reported that for every 4 queries, ChatGPT consumes half a liter of water. Think about the fact that the site has over 220 million visitors every month, and you can do the math and understand why cities near AI data centers have seen their water costs nearly double in less than a decade.

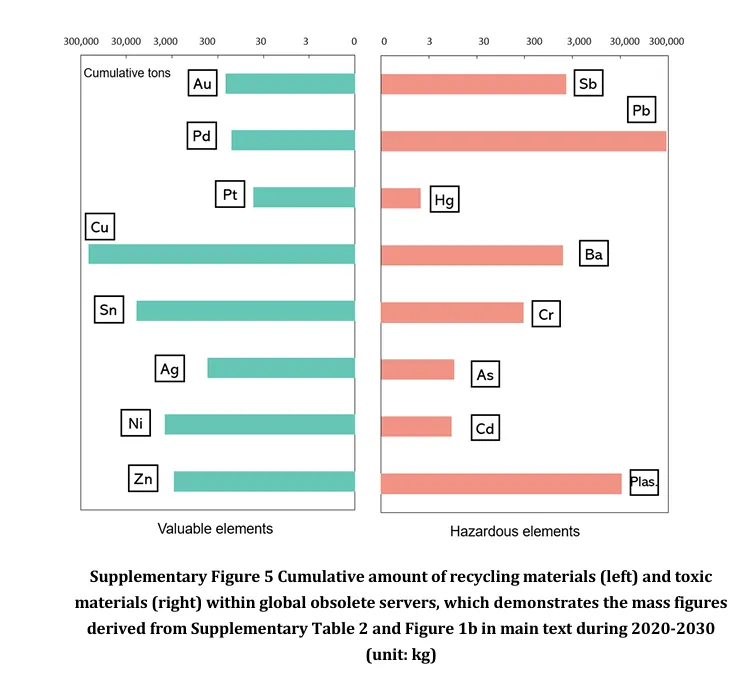

The research estimates that by 2030, this e-waste will contain nearly a million tons of lead, 6,000 tons of barium, and concerning amounts of cadmium, antimony, and mercury, adding a considerable amount of toxic elements into the environment—all with well-documented risks to soil, water, and public health.

The researchers don’t say whether companies and governments are doing enough, but there’s a financial angle too that can be beneficial. Metals like gold, silver, and platinum that are used in these discarded servers also represent significant financial potential if recovered. The study estimates that proper recycling of these metals could inject $70 billion into the economy, an incentive for advancing e-waste recycling infrastructure.

The study also explains that countries without access to the latest chips may generate up to 14% more e-waste, as they’re forced to use less efficient hardware.

But there are some solutions that may help tackle the problem. The researchers argue that extending server lifespan through enhanced maintenance could reduce the volume of e-waste by 58%, and reusing specific components would further cut waste by 21%.

Additionally, outdated AI servers could be repurposed for lighter tasks such as educational projects or basic web hosting instead of being thrown away, diverting them from waste streams and maximizing their utility.

This is turning into a priority for environmental groups around the world. Energy analyst Alex de Vries, founder of Digiconomist, told Decrypt that it is important to work on solutions before the negative impact of the AI industry is too hard to control.

“Right now, the numbers are small, so you can argue, ‘Why do we need to put this very high on our agenda if it’s still small?’” de Vries said. “But the thing is not going to stay small for very long.”

Edited by Andrew Hayward