This first appeared in Lit Hub’s Craft of Writing newsletter—sign up here.

Article continues after advertisement

The fullest day I know of begins with taking a portrait of a stranger in the middle of nowhere by 10 a.m. I do this while walking the historic roads of my home country, Japan. At 8 a.m. I set off with the goal of clocking some 20-40 kilometers, and by 9:50, I usually still haven’t taken that portrait. So I manically duck into whatever shop might be along the road (a tatami mat weaver, a gardening tools shop, a convenience store), or I’ll yell out to a farmer working their field: Good morning! Uhh, can I take your photo?! More often than not, they’re bemused (me, my quite obviously non-Japanese face, the fact that I’m in the middle of nowhere) and are happy to chat, and soon thereafter they’re happy to be photographed.

That unlocks the first creative act of the day, and the rest flow as easily as the walk itself. I’ll talk with a dozen people, all the while dictating into a growing note on my phone. I talk with the owners of old-style mid-century Japanese cafes—kissaten—and barbers and vegetable shop proprietors and multi-generational family members of historic inns. I talk with little kids commuting to or from school, bopping alongside the road, often shy but mostly eager to engage, however slyly. I tell them their town is lovely (something more people should say to more kids; and I mean it). One responds, “And just what the hell are you?!,” with a squeaky voice hidden behind an umbrella.

I have been living in Japan for twenty-five years and this talk comes easily, even in the countryside where folks might carry a thick accent. *Howdy*. I plow through. Deploy historic facts. Try to show I’m not a complete unknown in these parts, and though I don’t look like a local, I know a bit of this or that, enough to be considered a subtle ally, however cautiously.

Old men clip their hedges and I ask them what their town used to be like twenty, thirty years ago. We talk about depopulation, aging population. A social issue where Japan just happens to be on the forefront, but one which most of the world is—or will soon be—contending with. Like lost birdsong, those I talk to speak of the joyful shrieks and laughter of children that used to be everywhere, now gone. Gone, probably, for a good long while as these towns and villages vanish from maps and municipal records.

When I’m not talking, just walking (which is most of the time), I try to cultivate the most bored state of mind imaginable. A total void of stimulation beyond the immediate environment. My rules: No news, no social media, no podcasts, no music. No “teleporting,” you could say. The phone, the great teleportation device, the great murderer of boredom. And yet, boredom: the great engine of creativity. I now believe with all my heart that it’s only in the crushing silences of boredom—without all that black-mirror dopamine — that you can access your deepest creative wells. And for so many people these days, they’ve never so much as attempted to dip in a ladle, let alone dive down into those uncomfortable waters made accessible through boredom.

For me, from this boredom—this blankness of mind as I walk past sometimes fields and sometimes giant gambling pachinko parlors—words flow. I can’t stop them. My mind begins writing about what we see and refuses to shut up. That gap created by a lack of artificial stimulation is filled—thanks to the magic plasticity of our brains—with words and more words. Without Candy Crush, an inverted event horizon spawns, and out shoots: thoughts. I dictate as I walk. From afar, it looks like I’m either on a board meeting call with a CEO or am insane. Amidst all of this, in the lulls of dictation, I photograph—people, objects, mountains, trees, stumps, deer, shrines, temples, dogs depressed and dogs joyful, homes well used and those abandoned.

Eventually, I arrive at an inn or hotel (my favorites are anonymous so-called “business hotels,” cheap things dotting the archipelago, uniform, dependable, with fast internet and washing machines and, most importantly, silence). My feet? Hot in spots, a bit wonky, eager to shed their shoes. Each night, I spend three, four, or five hours collating the photographs, compiling my notes, doing laundry, creating an archive. By the time I sit down at night, my body is tired but my mind—since I’ve been dictating throughout the day, collecting moments and snippets of dialogue—is electric, like a crazy horse kicking at a barn door. It kicks the door open and off we go—writing two, three, four thousand words. They get edited into something mildly coherent, paired with a dozen photographs, and sent out in what I call a “pop-up newsletter.”

That is: a newsletter bounded by time, starting on day x and finishing on day y, at which point I delete the thing (including the email addresses of all the subscribers). Why delete everyone? Because a pop-up newsletter is a fresh start, requiring enthusiastic consent. Readers have asked to be automatically signed up for all of my pop-ups but that goes against the philosophy of them — they’re meant to be a thing, an event, and hitting “subscribe” is part and parcel of the process. And, anyway, being unsubscribed is a kind of gentlemanly gesture—like something Dick Van Dyke might do if he wrote newsletters—we seem to have lost in most online experiences. Here is my promise: x-number of emails, nothing more, nothing less. The result? Crazy high open rates because people are excited to be there.

I now believe with all my heart that it’s only in the crushing silences of boredom—without all that black-mirror dopamine—that you can access your deepest creative wells.

I walk for weeks at a time. The longest walk I’ve done was about forty days. Do this day after day—the intense mileage, the intense wordage, the looking, the talking, the boredom-bathing, the wringing texture and life from a day—and you are changed. It’s impossible not to be. The whole thing, an ascetic practice. I even shave my head like some performative mendicant, one who lives off stories as alms. I’ve been doing walks like this for six years now, and they’ve made me more patient, kinder, more optimistic about the world, people, more amazed than ever at how many goofy-ass animals (monkeys jumping off bridges, tiny bears running like little pigs, mountain crabs that have no right to exist up on a lookout) are out there in the woods.

But perhaps what I’ve gotten most out of these days is an understanding of “fullness.” That is, how much potential exists in the most banal-seeming of itineraries. How everyone has a story worth listening to, even if just for five minutes. How the details and patterns of life go unseen with a head stuck in a phone. And how—after having walked for eight straight hours, heavy pack on my back (multiple cameras, laptop, rain gear), and then having written for hours, edited, banged the text into a publishable state, added photographs, and hit send, finally at the end of the day)—when my head hits the pillow at night, I smile knowing there was no fuller day to be had, no better way to have played the cards dealt to me on that morning.

I realize now I didn’t know fullness before I started walking like this. The walk taught me fullness. It’s good like that, the walk. Walking. I’ve now got hundreds of “max full” days under my belt. You carry the feeling of those days back to your everyday life. You now have an archetype for a fully “used up” day. That’s a powerful thing, and one that can’t be learned through description alone. It must be felt in the bones after mile twenty, on the tenth day of doing twenty miles, on the tenth day of banging out a text, collimating the experience of connecting with strangers, feeling the sonder of those you pass, melding the day into words, pairing those words with images, creating a complete “object” or piece as it were. And then pushing it out into the world (the publishing at the end of the day creates a kind of stakes that I find is critical to eking out that last drop of fullness).

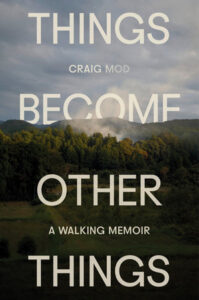

Anyway, I like these walks, these big dumb walks alone along old paths, paths once full of life, now a bit somber, but still beautiful in their own rusted ways. What happens to these pop-ups? Sometimes they become the grist for a book. I took a walk four years ago during the height of COVID. A thousand kilometers along the old paths of a countryside peninsula called Kii. The essays from that walk became the basis for Things Become Other Things, a story of a walk but also a story of a friend, someone I had never forgotten but wasn’t able to look back at until the walk helped me do so, the boredom gave me the courage and permission to peek.

The fullest kind of day I know begins setting off at 8 a.m. with some big mileage in mind. But sometimes the energy of the walk keeps going, well beyond the walk itself. Years later, slowly and then suddenly, it is a book, a thing in hand, something much bigger than a walk alone.

____________________________________________

Things Become Other Things by Craig Mod is available via Random House.