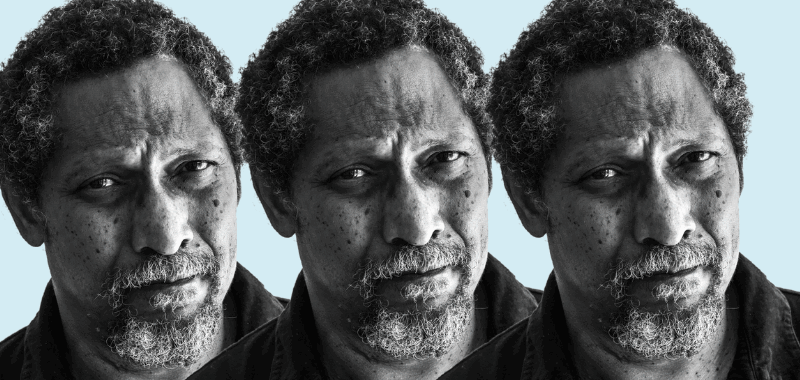

Earlier today, the 2025 Pulitzer Prizes were announced and Percival Everett’s James was declared the winner for fiction. This came as no surprise to anybody even vaguely tapped into the literary scene: in addition to winning the National Book Award for Fiction, James won the Kirkus Prize and was a finalist for the Booker Prize, garnering rave reviews across the board.

As I was listening to the prizes being read out today, I was struck by something else: there were four finalists. Every year in recent memory, even the “no award” debacle in 2012, has had only three finalists. So why were there four this year?

Anybody who has followed other Pulitzer Prizes over the years might recall that, in 2010, this happened in the drama category when Next to Normal was the surprise winner over three other nominees. Charles McNulty, the LA Times theater critic who had been on the jury that year, wrote a column about it, and while that column seems to have been lost, Patrick Healy wrote about the column for the New York Times and quotes McNulty that the board ignored “the advice of its drama jury in favor of its own sentiments.”

And a quick perusal of the Pulitzer administration practices seems to confirm that the five-person jury delivers the Pulitzer board three picks in their respective categories: “Each jury is required to offer three nominations but in no order of preference, although the jury chair in a report accompanying the submission can broadly reflect the views of the members.”

Then, here’s the fun part: “Awards are made by majority vote, but the Board is also empowered to vote ‘no award,’ or by three-fourths vote to select an entry that has not been nominated. If the Board is dissatisfied with the nominations of any jury, it can ask the Administrator to consult with the chair to ascertain if there are other worthy entries. Meanwhile, the deliberations continue.”

Okay, a bit unclear there! But the way I read this: the Board can vote ‘no award’ (see 2012) or select a fourth book on their own (or play) that wasn’t nominated or ask the jury for “other worthy entries” that the Board might be willing to entertain. And just to be certain, I confirmed this with a recent Pulitzer jury member.

No matter how you slice it, this says to me to the 2025 Fiction Jury turned in what would have been a world-shaking all-woman trio of finalists in a year when one novel by a male writer has taken up quite a lot of the available oxygen, and the Board—one way or another—said “No.” Which is not to diminish the staying power of Everett’s book… But rather to wonder if a bit more bravery or even just ambition or, more plainly, willingness to be weird on the part of embattled well-meaning institutions might be called for, in times such as these.